Straight From The Horses Mouth - the extraordinary cruelty of the bit

While beating a horse with a whip is considered animal abuse by those with common sense, it’s the other obligate tool of the racing industry, the bit, that delivers the most harmful blows of all.

What is the bit?

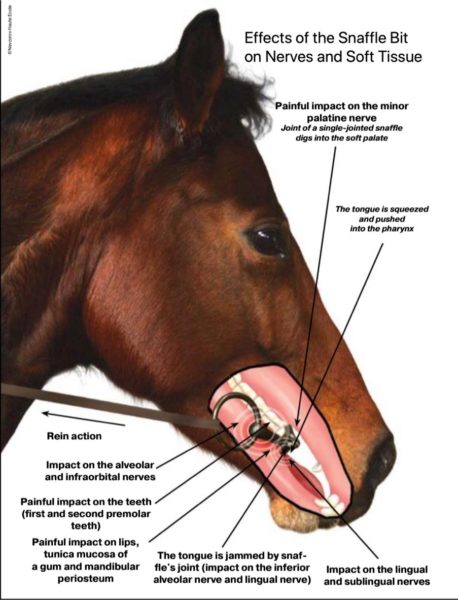

Designed to control horses by applying pressure in the mouth, the bit is a metal device held in place in a horse’s mouth via a bridle then attached to the reins or a lead. The bit is forced against areas of the horse’s mouth that are known to have an extremely high density of sensory receptors, via a rider’s pressure through the rein. The only possible experience for a horse of this pressure from the bit in its mouth is pain.

Studies (further detailed and referenced below) show bits cause many serious welfare consequences for horses. Injuries from bit use range from lesions in soft tissue and bruising, to chronic impediment of a horse’s ability to breathe or swallow normally. The bit induces such high levels of pain which, due to its intensity and location, can override all other pain a horse might experience, including fear. It’s this attribute that makes bits the highly effective, albeit cruel instrument of control they are. Bits allow riders to push horses well past safe physiological limits, control them in painful and frightening circumstances, and are a contributing factor, if not the cause of many of the falls, shattered limbs, asphyxia and sudden death experienced by horses on the racetrack.

Proponents of the bit suggest it is merely a tool of “communication”, being more or less gentle depending on the hands that use it. In truth, a bit is no more a tool of communication for the horse than a thumbscrew or medieval rack is a tool of communication for people. In other words, a horse’s response to a bit should not be taken as solicitation or agreement by the horse of the “requests” of a rider but is always, and only because of the pain the bit induces.

The bit sits in the interdental space, or bars – the toothless area in the horse mouth – directly in front of the first and second premolars.

Pressure to the bit by reins or lead causes pain directly in the horse’s mouth, allowing control of a horse’s head by a rider or handler. Much like turning the steering wheel of a car, drawing pressure on a rein forces a horse to bend towards the same side. But unlike a car - an inanimate unfeeling object – the horse’s compliance to rein pressure is always a submission to pain.

Richly innervated and densely packed with sensory receptors, pressure to the interdental space induces sensations that are consciously and acutely felt by the horse (1). The pain of the bit is immediate and intense and captures the attention of a horse in a way that nothing else can.

Contrary to certain thinking, there is no way to use a bit “gently”. The presence of a foreign body in the horse’s mouth, especially one made of metal, will always be uncomfortable. Any amount of pressure by such an object against the soft tissues of the mouth, will result in pain that quickly intensifies (1).

There is a myth that suggests ‘an ounce in the hand is an ounce in the mouth’. The bit being of rounded metal, effectively reduces the area of contact. Small contact points mean increased pressure (2). Thus, any rein or lead pressure will be magnified many times over in the horse’s mouth.

In the ‘St Petersburg Study’ on bit damage (3), researchers calculated the effect of rein draw as force per square centimetre in a horse’s mouth. This research shows the tremendous forces that are inflicted upon the mouth of the horse by the bit:

- ‘Standard’ contact to the mouth via the reins, which is the minimum level for force, has been shown to range from 50 – 100 kg per square centimetre

- For an average force jerk – from 180 kg to 220 kg

- For a strong jerk: over 300 kg

The real-life consequences of these sorts of extreme forces against living tissues result in significant physical and psychological harm to the horse.

How harmful are bits?

The welfare considerations of controlling a horse through bit-induced mouth pain are numerous (1).

The following list is some of the common injuries caused by bit use:

- Acute trauma to the mouth, including lacerations, ulceration, bruising and impeded blood flow, resulting in damage to the tongue, gums, soft palate, cheeks and teeth. Studies show these injuries mostly go unnoticed by riders, as blood is often not present outside the mouth (7). In a study conducted on harness racing horses, 84% of the horses showed oral lesions caused by the bit, with 20-60% of these lesions being categorised as moderate to severe (7)

- Impairment of the ability to breathe normally and swallow (4,5,6)

- Psychological torment from pain or anticipation of pain (1,5)

- Psychological torment from being unable to draw breath, resulting in the sensation of suffocation (6)

- Bleeding from the lungs due to changes in airflow and abnormally high suction pressures on the lungs (4)

- At least sixty-nine aversive behaviours are attributed to pain caused by the bit (1) these include the commonly seen behaviours of racehorses; gaping mouth, tongue lolling, excessive salivation, crabbing, excessive repetitive head shaking etc

- The behavioural indications of pain, commonly accepted as “normal” ridden horse behaviour are not seen in the unridden or wild horse (1,3,9,10)

- Damage resulting in bony changes, or bone spurs, within the bars or interdental spaces of the skulls of horses ridden with bits - proof of long-term damage. These bony changes are known to be extremely painful and are not found in wild horses or horses who haven't been ridden with bits (1)

Aside from the immediate physical pain mentioned, the bit induces fear and panic by affecting the horse’s ability to draw breath resulting in sensations of breathlessness and suffocation (4). This is particularly concerning for racehorses, as a galloping horse takes two and a half forceful breaths a second, even transient airway obstruction can quickly cause serious consequences. (4)

The horse is an obligate nose-breather and is forced to struggle for breath when the lip seal is broken by the bit. This impediment of normal breathing and function of larynx, throat and lungs is believed to be a cause of asphyxia, breathlessness, bleeding in the lungs, stumbles, falls, panic, fear and sudden death in racehorses. (1,4,6)

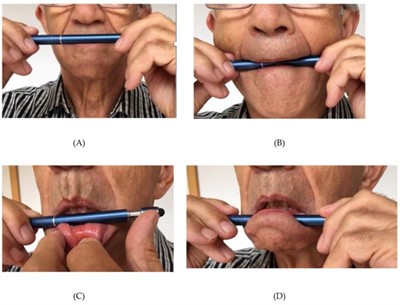

An experiment for the reader

To illustrate the pain caused by the bit, welfare researcher and scientist David J Mellor offers a simple experiment, The ‘Mellor pen test.”

The test simulates bit pressure applied to the gums of the interdental space of the horse. Gums are exquisitely sensitive to painful stimuli, including compression. Rein tension transferred to the bit in contact with the gums of the interdental space causes pain.

(A) Position 1: Hold the pen in front of your mouth;

(B) Position 2: Open your mouth, place the pen where the upper and lower lips meet on each side, and then push the pen towards the back of your throat. No gum contact, no significant pain;

(C) Position 3a: Roll your bottom lip down and locate the pen on your gum, below your central incisors;

(D) Position 3b: Now release your lip and with both hands holding the pen, apply compressive pressure to your gum, carefully increasing the pressure in steps from very low until the pain is too intense to continue. How much compression-induced pain could you stand?

What types of bits are used in racing?

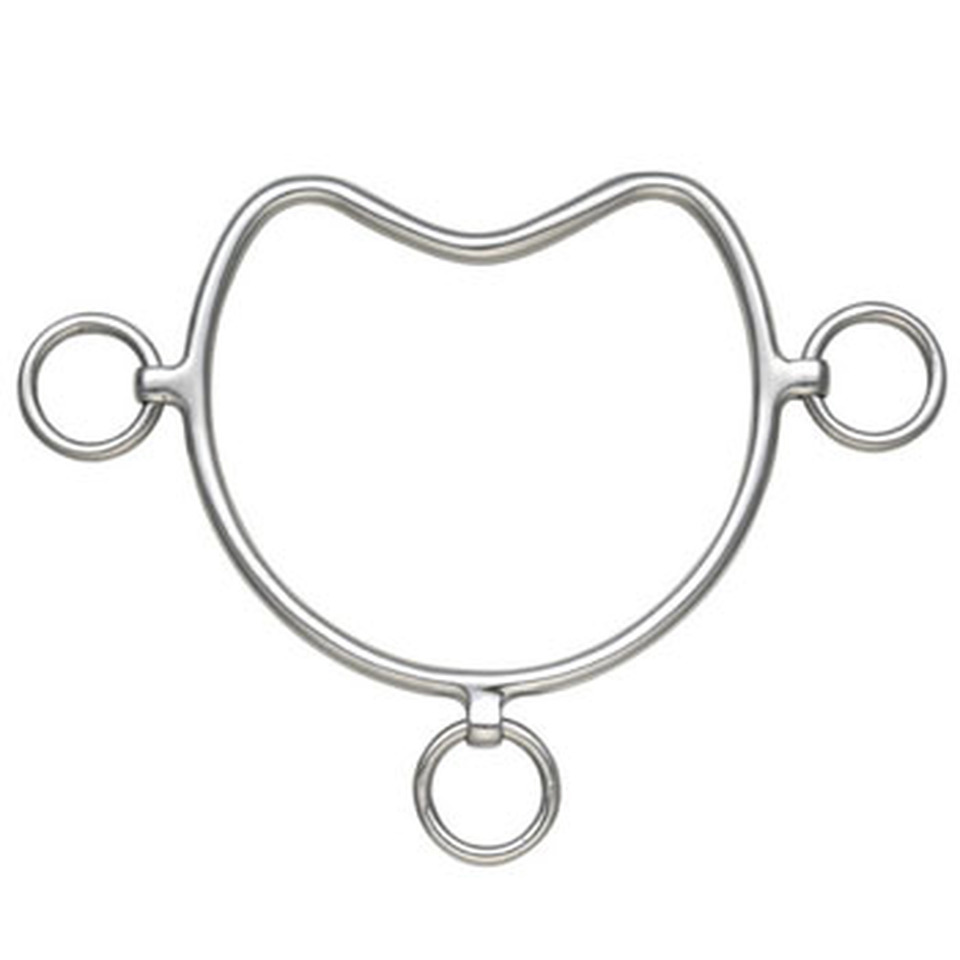

The most commonly used bit in racing is the Dexter ring bit. It combines the action of a snaffle with an added ring. The extra ring limits the nutcracker action of the snaffle but adds considerable leverage to the horse's mouth. In addition, being of very thin steel, it increases pressure to the mouth significantly, giving added force in stopping and steering the horse.

Even without the added ring, the snaffle’s main action is to drive pressure into the highly innervated parts of the horse’s mouth – in particular, the interdental space or bars.

The joint in the middle has the added action of protruding up into the soft palate or crushing pressure onto the tongue, depending on the horse’s head position.

All parts of the mouth are affected; lips, teeth, gums, tongue, inner cheeks and cranial nerves of the mouth, face and head.

Ironically, the snaffle bit is considered a “gentle” bit, probably only because of its crude simplicity which hasn’t changed in nearly 5000 years (2). Simple however, should not be confused with gentle.

The snaffle bit is far from gentle, especially when used on racehorses. A Finnish study (8) showed that the snaffle bit caused greater incidence of mouth injuries in racehorses than horses ridden with significantly “harsher” bits in other sports. These injuries were more numerous and ranked higher in severity of damage.

According to the study:

“Racehorses with snaffle bits were predisposed to significantly higher severities and prevalence of oral trauma than were polo ponies in gag bits… Racehorses also had higher severities of injuries in the commissures and bone spurs” (8)

A horse, like any living being, will try to defend itself against pain. The area of the interdental space is so rich with sensory receptors and unprotected by any muscle, fat or bulky soft tissue that horses experiencing severe pain will try to put their tongue over the bit to seek relief. While not rendering them completely free from pain, the tongue over the bit provides some brief relief in the most sensitive areas, mainly the corners of the mouth and the bars. Such behaviour is commonly seen in racehorses. This slight reduction from the all-encompassing agony means a horse can rebel a little against the assault - the rider temporarily losing the ability to inflict the most acute pain, resulting in lower rates of control.

Unfortunately, racing has devised a particular remedy for this common problem: tongue ties. The ties are used to prevent the horse from being able to put their tongue over the bit, creating another set of welfare considerations, including the inability to escape pain at all, blood flow impediment to the tongue, breathing issues and further trauma to the jaw and mouth. Read more on tongue ties here.

It should be mentioned that there is another bit, additional to the snaffle and dexter that is used when leading racehorses. The Chifney, or so-called anti-rearing bit.

The Chifney anti-rearing bit is so severe in its action that veterinarians caution for it to be used exceedingly sparingly, reserved only for rare or extreme circumstances.

Injuries caused by the Chifney bit are extremely severe. Made of thin metal with a particular shape that depresses the tongue, a Chifney bit easily lacerates tongues from the extreme pressure it inflicts. It causes instant injury with little effort, resulting in permanent damage to the bars or harm to the tongue, and delivers what can only be described as intense pain, hence the serious warning by professionals against its use.

The use of this barbaric tool by the racing industry highlights racing's inadequacy towards horses' welfare. It is incomprehensible that such an injurious and dangerous tool ever be deemed “necessary and normal” and further demonstrates the level of unprofessional and cruel training practices in the racing industry.

Will bit use ever be reformed in racing?

Unlike the whip, the chance of a reform of bit-use in racing is doubtful.

With the current racing practices, handling a horse on the track without some sort of blinding pain control would be impossible. Bit use is obligatory to force a horse to ignore its natural instinct for self-preservation: to jump dangerous obstacles, run to the point of breakdown and asphyxiation, and participate in painful and terrifying activities.

The speed with which young horses are brought into racing, with insufficient, improper handling, and being radically underdeveloped, proves the real attitude of the racing industry towards horses.

Using humane training techniques takes investment of time, consideration and knowledge of a trainer. For those who value horses as feeling beings deserving of respect, and at the very least freedom from unnecessary suffering, this is a fair and normal price to pay to ensure the horse’s welfare.

It is hard to see how this investment of time and education would make sense to the racing industry. With no racehorse expected to have longevity, any time spent on considerate or careful horse training is time wasted since turnover of horses in racing is already extraordinarily high. Controlling horses' bodies through the pain of the bit is cheap, instant, guaranteed and requires no special skill.

Why would the industry change when pain already works so well?

If the bit is so harmful, why is it still in use?

Bits have been the main feature of horse control since the beginning of horse subjugation. Bits have remained virtually unchanged for thousands of years and are so entrenched in our collective psyche that it is rare to see an image of a horse without one.

Perception becomes reality, and the illusion of a somewhat co-operative, excited, prancing racehorse has been actively portrayed as “normal” in the minds of the public.

Research by experts unquestioningly show that those very same behaviours; the wild eyes, teeth grinding, gaping mouth, salivation, jigging, tongue lolling, head shaking, rearing, straining neck, tail swishing are behavioural signs of extreme pain and fear in a horse and can’t be discounted as “normal” but are clear indications of compromised welfare (1).

Because the general horse-loving public and non-racing horse riders often do not recognise the behaviours that indicate pain caused by bits, the magnitude of the problem is hugely underestimated. (1)

In general, people don’t want to contribute to cruelty to horses, so as awareness grows of the suffering, bit use must come under question.

Unsolicited and externally induced inescapable pain can only be described as cruelty and is the honest summation of bits effect on horses. The increasing awareness of the injuries and harm caused by bits, and recognition of behaviours that show a horse is experiencing pain, means that bit use must be recognised as being cruel and, as such, is an unacceptable breach of equine welfare.

How long can it continue that controlling horses by bit-induced pain is a commonly accepted practice?

Ignorance and denial about the harm of bits is partially due to the outdated belief that some level of pain experienced by a horse during horse training and riding is a “necessary evil”.

The excuse that there is no other way to train or ride horses, except through discomfort or pain has been debunked. Massive industry growth in the areas of bit-less horsemanship and other welfare-conscious training techniques show the use of bits is completely unnecessary in our pursuits with horses. Furthermore, these welfare-based improvements in the wider non-racing horse community highlight the need for better overall understanding of horses in general, including how horses learn and furthermore, what constitutes acceptable humane training practices.

Additionally, the advancements in equine science, psychology, training and welfare show the real level of harm has been grossly underestimated. Bit induced pain and its consequences are, in truth, so extreme it cannot be considered anything but an unacceptable result of our use of horses.

The question that should come to our minds is, if you cannot train a horse without pain and suffering, should you train a horse at all?

A last thought

Bits are the cause of extraordinary suffering in ridden horses (1) leading to serious welfare consequences that shouldn't be ignored. Despite this, the racing industry is unlikely to change its practices, since it is pain that allows them to race horses in the first place. Investing time to allow for pain-free training practices, or allowing for the full repair of injuries before being raced again, or for a horse to finish physically maturing at the age of six before being put in training will mean the industry cannot operate as it does today.

It should be remembered that there is no “gentle” use of a bit and it is racehorses that are at highest risk of harm. The industry, with its high turnover of horses, is unlikely to invest time into humane training techniques as consideration of the long-term welfare of the horses is not necessary.

By performing the Mellor pen test on themselves only briefly, a person can experience some idea of the agony bit use causes horses, even with light pressure (1). This must raise the question in our minds; how much pain is acceptable in our use of horses, especially when there are far more effective ethical options for training available?

If by eliminating bits, and improving training by any one of several modern welfare-based training methods means that the racing industry cannot conduct their normal practices, or in other words, if they cannot force horses to run without the infliction of extraordinary cruelty and pain, is it ethical that they should be allowed to practice in our society at all?

The removal of bits, the primary source of pain control of horses, would mean a complete overhaul of racing industry practices. Pain-free methods mean frightened, injured, poorly trained, undeveloped horses could not be forced to race as they do with bits, and trainers would have to seek genuine cooperation and understanding from horses. This takes care, time and knowledge - something the racing industry is fundamentally lacking as a profit-driven industry. Unfortunately, for the horses trapped in racing this means that bit reform is impossible and reinforces CPR’s position that whilst welfare improvements can be made in many areas, ultimately, horse racing as an industry can never be made kind for the horses it depends on to exist.

References

- Mellor, D., 2020. Mouth Pain in Horses: Physiological Foundations, Behavioural Indices, Welfare Implications, and a Suggested Solution. [online] Available at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10040572.

- Clemence, J., 2010. To Bit or Not To Bit?. [online] Naturalhorseworld.com. Available at: <https://www.naturalhorseworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/tobitornottobitJClemence.pdf

- Nevzorov, A., 2012. Equestrian Sport: Secrets of the "Art". 1st ed. St Petersberg: Nevzorov Haute Ecole, pp.147-165.

- Cook, W., 2002. Bit-induced asphyxia in the horse. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 22(1), pp.7-14.

- McLean, A. and McGreevy, P., 2010. Horse-training techniques that may defy the principles of learning theory and compromise welfare. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 5(4), pp.187-195.

- Mellor, D. and Beausoleil, N., 2017. Equine Welfare during Exercise: An Evaluation of Breathing, Breathlessness and Bridles. Animals, 7(12), p.41.

- Tuomola, K., Mäki-Kihniä, N., Kujala-Wirth, M., Mykkänen, A. and Valros, A., 2019. Oral Lesions in the Bit Area in Finnish Trotters After a Race: Lesion Evaluation, Scoring, and Occurrence. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 6.

- Mata, F., Johnson, C. and Bishop, C., 2015. A Cross-Sectional Epidemiological Study of Prevalence and Severity of Bit-Induced Oral Trauma in Polo Ponies and Race Horses. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 18(3), pp.259-268.

- Cook, W. and Kibler, M., 2018. Behavioural assessment of pain in 66 horses, with and without a bit. Equine Veterinary Education, 31(10), pp.551-560.

- McLean, A. and McGreevy, P., 2010. Ethical equitation: Capping the price horses pay for human glory. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 5(4), pp.203-209.

Additional Resources

Anthony, D.W. and Brown, D.R. (2011). The Secondary Products Revolution, Horse-Riding, and Mounted Warfare. Journal of World Prehistory, 24(2-3), pp.131–160.

Brown, D. and Anthony, D. (1998). Bit Wear, Horseback Riding and the Botai Site in Kazakstan. Journal of Archaeological Science, 25(4), pp.331–347.

Cook, W.R. (1999). Pathophysiology of bit control in the horse. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, [online] 19(3), pp.196–204. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0737080699800677 [Accessed 6 Nov. 2020].

Frcvs, W.R.C. (2013). 1 BIT-INDUCED FEAR : A welfare problem & safety hazard for horse and rider. [online] www.semanticscholar.org. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/1-BIT-INDUCED-FEAR-%3A-A-welfare-problem-%26-safety-for-Frcvs/6434432322973d3e9890fc6f310d0ddb5cfaaf1c [Accessed 17 Mar. 2022].

Jeffrey, D. (2009). Oral health in equidae : fundamental equine gnathology : fostering a positive and coherent relationship with the horse. King Hill, Idaho: Dale Jeffrey ; Glenns Ferry, Idaho.

Johnson, T. (2002). Surgical removal of Mandibular Periostitis (Bone Spurs) Caused By Bit Damage. Researchgate.

Manfredi, J., Clayton, H. and Rosenstein, D. (2005). Radiographic study of bit position within the horse’s oral cavity. Equine and Comparative Exercise Physiology, 2(3), pp.195–201.

State Institute of Health Protection of Saint - Petersburg; St Petersburg study: Isakov V. D. & Sysoev V. E.

Nevzorov, A. (2012). Equestrian Sport: Secrets of the “Art.” 1st ed. St Petersburg: Nevzorov Haute Ecole, pp.47–69.

Tell, A., Egenvall, A., Lundström, T. and Wattle, O. (2008). The prevalence of oral ulceration in Swedish horses when ridden with bit and bridle and when unridden. The Veterinary Journal, 178(3), pp.405–410.