Supporters may recall, back in November 2020, we published an article titled “Racing Tasmania Admits Racehorses are Routinely Shot in the Head” – available here.

Within the article, we drew attention to an interview with the then General Manager of the Office of Racing Integrity (ORI) and Director of Racing John King, who admitted on ABC Morning Radio that a “significant” number of two, three and four year old racehorses are shot in the head due to simply not being fast enough – referring to the issue as “an unfortunate truth”.

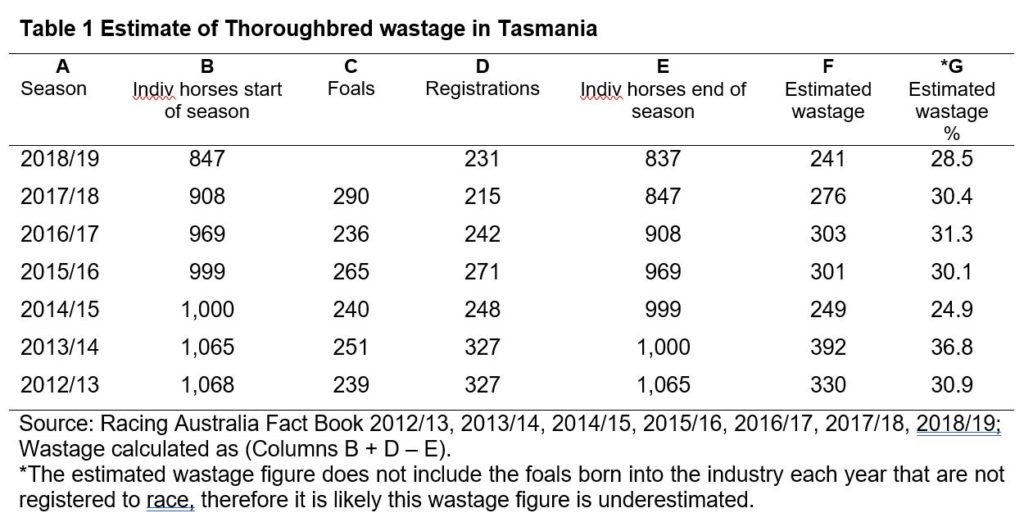

So, we crunched some numbers and found that on average, 299 horses vanish from Tasmania’s thoroughbred racing industry every year.

Mr King did shed some light on where some had gone, when he stated that 59 Tasmanian thoroughbred horses had been euthanised due to injury or illness that racing year.

This figure raised serious red flags, as according to our research of stewards reports for that racing year, 2019/20, not a single horse was reported to have been killed due to injury – at least on race day. Could all 59 injuries resulting in euthanasia have really occurred away from the racetrack?

Our article led to us having a discussion with the office of Tasmanian MP Andrew Wilkie, who too was appalled and outspoken when he heard the ABC interview.

Mr Wilkie subsequently put forward some questions to Tasmania’s Minister for Racing at the time, Jane Howlett, regarding:

– Mr King’s comments;

– our findings on the number of horses vanishing from racing each year;

– auditing procedures to claims horses are “retired” and,

– breeding incentive programs.

The answers to these questions came from Mr King’s replacement at the ORI, Tony Latham in June 2021. NB: Mr Latham has since been removed from his role and placed under investigation for misconduct for other matters.

Question 1

How many of those (59) deaths were caused by injuries that were sustained or likely sustained as a result of racing, trials and/or training?

ORI Mr Latham’s answer:

36 horses were euthanised from injury – The majority of those euthanised was training related with a few injuries sustained whilst spelling. There were no racetrack deaths in 2018/2019 or 2019/2020 financial year.

7 Horses were euthanised from illness.

16 horses were euthanised by the owner’s request due to not suitable for rehoming or behavioural issues.

So, most of the 36 life-taking injuries were sustained during training (not racing) in Tasmania alone, a tiny industry comparative to other states. This is a sobering statistic when you consider our Deathwatch Report finding of one horse being killed due to racing-related injuries every 2.5 days Australia-wide is made up almost entirely of injuries sustained on race day. If deaths caused from training and trials were required to be reported across the country, it is horrifying to imagine how many actual horses are being killed due to racing related injuries each year. Having said this, considering the high number of horses who leave the racetrack injured/lame, it is highly unrealistic that none of those horses would have been euthanised from those race day injuries once being taken from the track.

Question 2

Based on figures obtained from the Racing Australia Fact Book, an average of 299 thoroughbred horses have vanished from racing in Tasmania each year over the past seven years – see Table 1 below. This is approximately 30% of the horses registered to race in Tasmania – a figure similar to that of the country average. Mr King acknowledged that a “significant” number of two, three and four-year-old racehorses are shot in the head due to simply not being fast enough. How many of the horses taken out of racing each year suffer such a fate?

ORI Mr Latham’s answer:

Regarding your comments about horses ‘vanishing’ over the past seven years is not the case, and comments regarding a significant number of two, three- and four-year-old horses destroyed due to not being fast enough is incorrect. The data provided by Racing Australia reveals that between 1 July 2019 and 30 June 2020, sixteen (16) four-year-old named horses were retired from the racing industry. Three (3) were euthanised due to injury, two (2) were retired for breeding, eleven (11) were retired for either equestrian / pleasure / working / companion horse / breeding (non-racing).

So, is Mr Latham stating that the Racing Australia Fact Book figures on the numbers of horses being bred and raced each year (where our figures come from) is incorrect? Is he also stating that his predecessor Mr King lied in his ABC interview or that he was ill informed? As to the data provided by Racing Australia on four-year-olds – well, that accounts for 16 of the several hundred to have vanished from racing that year, and whether accurate is questionable considering the data comes from owners claims on a form.

Mr Latham went on to state:

In 2018/2019 financial year there were 742 named horses notified of being retired, deceased/euthanised or retired as breeding

In 2019/2020 financial year there were 537 named horses notified of being retired, deceased/euthanised or retired as breeding.

Of all the claims made by racing authorities, this had to be one of the most absurd. The figures we calculated in Table 1 demonstrate that on average 299 horses vanish each year from Tasmania racing. Our figures are based on information provided in the Racing Australia Fact Book, which indicates in the 18/19 racing year 241 named horses vanished from racing in Tasmania. The ORI claims that 742 were retired/deceased/euthanised/breeding. Is the ORI saying the problem is over three times greater than what we found?

Even more absurd, according to the Fact Book, there were only 847 horses in total at the beginning of the 2018/19 racing season in Tasmania. To lose 742 is a single year from racing to retirement/death/breeding is essentially to lose almost every single registered horse from racing and replace them. Mr Latham’s claim of 537 named horses notified as retired/deceased/euthanised/breeding the following year represents a similarly strange scenario.

Such figures make absolutely no sense, unless of course the situation in Tasmania is even worse than our findings suggest.

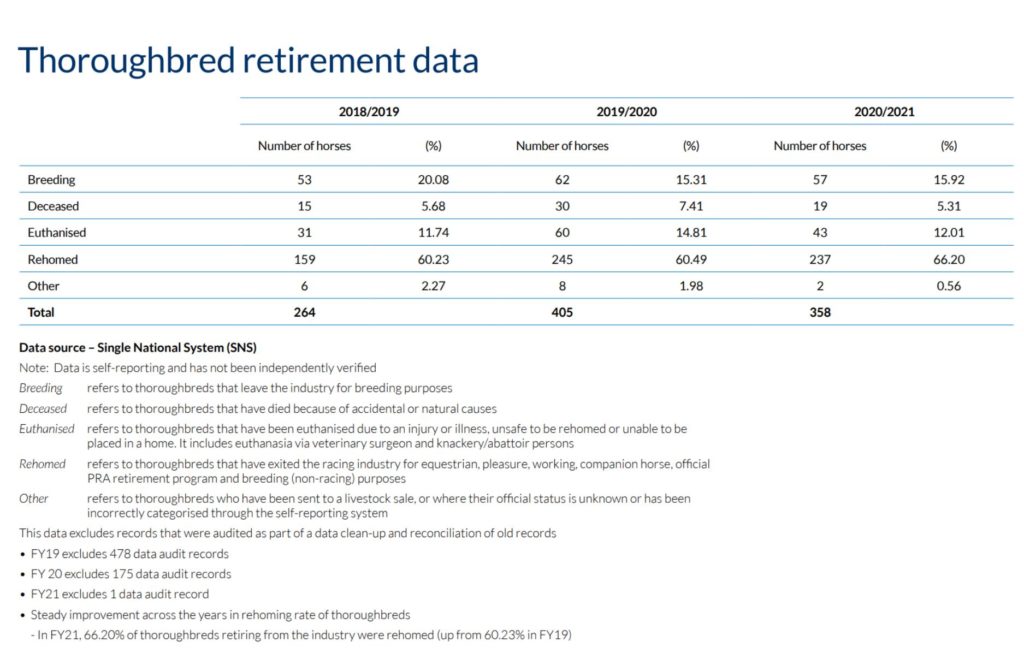

Finally, some light was shed on these claims once Tasmania’s own 2021 Annual Report was published – available here.

On page 19 they mention a “data clean-up and reconciliation of old records” under their retirement data chart.

Adding the “data audit records” to their chart figures adds up to the numbers Mr Latham provided in his response to Mr Wilkie. For example: in the 2018/19 racing year, according to the chart above, 264 horses were retired/deceased/euthanised plus 478 came from audit record clean ups – total 742, as claimed originally by Mr Latham.

So, there are two options here – either TasRacing are just making up figures to cover for the ORI’s very odd and concerning original claims, or they are actually cleaning up shop as they claim in the above chart (on gathering retirement data at least). If the latter is in fact the truth, then why did Mr Latham not mention this in his response? It appears to us that it never even registered to him that he was providing a figure that demonstrated that almost every single horse in racing was being taken out of racing each year due to death, ‘retirement’ or for breeding and replaced. If he acknowledged how large this figure was, would he not have explained it was due to a ‘data clean up and reconciliation of old records’ as now being claimed in the chart above?

It must also be noted that 2021 is the first time in the history of the TasRacing Annual Report, that they have published thoroughbred and standardbred horse retirement figures. This is a clear indication that increased pressure on TasRacing by animal welfare groups, some politicians and the general public has forced them to demonstrate at least some form of accountability. Previously, the term ‘retirement’ more frequently appears when discussing board members and pension benefits.

Of particular note in the TasRacing chart above:

Euthanised refers to thoroughbreds that have been euthanised due to an injury or illness, unsafe to be rehomed or unable to be placed in a home. It includes euthanasia via veterinary surgeon and knackery/abattoir persons.

Euthanasia is when a horses suffering cannot be addressed to give quality of life – not convenience killing, and should never be done in the terrifying horrors of a knackery or slaughterhouse. There also appears to be no requirement for the owner to prove they made any rehoming attempts at all, nor proof that a horse is dangerous.

The chart also claims the majority (over 60%) of thoroughbred horses are rehomed. Yet, it also states: Data is self-reporting and has not been independently verified.

Completing retirement forms is now compulsory, and the address to which a horse is being rehomed must be provided. However, these are not fact checked by the authority. A person retiring a racehorse can say anything they like on the form. Why would one admit they are killing horses once they no longer want them when they don’t have to? And why would John King, as the General Manager of the ORI, have stated in 2020 that a “significant” number of two, three and four-year-old racehorses are shot in the head due to simply not being fast enough? Of course, ‘not being fast enough’ is not one of the descriptions of what being ‘euthanised’ (killed) refers to in the chart above.

There is no way of knowing if the rehomed figures claimed by TasRacing are accurate, but history and the known difficulty of rehoming racehorses makes it a safe bet to assume they are not. At the very least, the figures provided by the ORI in the various stages of this brief inquiry about “retired” horses, gives the public virtually no confidence in the accuracy of their record keeping.

As a final note on the above chart: there is interestingly one very obvious statistic missing. Trainers and owners constantly profess their absolute love for the horses they use. Yet, there is no category for a trainer or owner who has kept their horse after ‘retirement’. According to TasRacing figures, every single horse used to race over the past three years either died, was put into breeding, was sent to a livestock sale, or was rehomed. It is of course entirely possible that some owners/trainers may have kept a horse in their care after racing, but the fact that this is not even a category suggests they would of course be the exception to the rule. Funny that.

Our final question to the Tasmanian Minister for Racing

The Tasmanian government has allocated $1.54 million toward the Tasbred incentives scheme designed to encourage Tasmanians to not only breed more thoroughbreds but to also race them as early as two, three and four years old. Considering there is a “significant” number of horses being killed each year for simply not being fast enough and the fact that racing horses before their skeletons are fully formed increases the chance of early injury and therefore death, is it not therefore against the industry’s and governments claims of taking animal welfare very seriously, to be encouraging bringing more horses into an industry only to be injured and/or killed at an age that is a fraction of their natural lifespan?

ORI Mr Latham’s answer:

The Tasmanian Government financial contribution to the TASBRED scheme strengthens the Tasmanian Racing Industry, providing incentives to increase breeding of racehorses in Tasmania, creating new jobs within breeding, racing, and associated primary industries. The TASBRED scheme in my opinion will not lead to an increase in animal cruelty as the horse population remains at a consistent level and the number of races held has not increased.

The TASBRED scheme will promote breeding in Tasmania which will strengthen the Tasmania thoroughbred population and in the longer term, this will decrease the number of imported horses coming into the state from the mainland.

This $1.54 million has now increased to $2 million for 2022. Even though retirement data, now officially published, shows approximately 300 thoroughbred horses alone (approx. 450 when horses from Tas harness racing are including), are in need of good homes each year, just in Tasmania, the Tasmanian Government doesn’t see incentivising more breeding to be a problem. Of course, these are just the numbers of horses who are retired after making it to the track in the first place. Plenty more who are bred do not. A horse’s natural lifespan is roughly 25 years. Where does TasRacing and the Tasmanian Government expect all of these horses to go? Sadly, we know the answer.

Cover image: Sneaky – a Brightside Farm Sanctuary resident, rescued from a Tasmanian racehorse trainer who was selling him for pet meat.

Greed is the fundermental reason for such cruelty.

Shame on the racing industry in Tasmania.we over here in Ireland will spread this up to date information.

There is always Karma.

Absolutely horrific .